This post contains affiliate links. If you click through and buy I will receive a percentage commission at no extra cost to you.

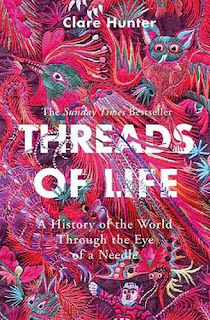

Hunter’s brilliantly informative and emotive look at the history of embroidery from the Bayeux Tapestry to the present day is the perfect mix of personal memoir and wider history. She considers the rise and fall of respect for the craft, the ways it has been used to comfort, strengthen, and protest, and the curatorial decisions that obscure so many great creatives. Arranged thematically, each chapter could be read in isolation, but the experience of reading cover to cover offers insight and a sense of the patterns of time.

We start with the Bayeux Tapestry, which is an example of many of these themes. Over the centuries it has been through many levels of popularity and respect. It has been dismissed at times as a piece of amateur work and criticised for its inconsistencies of style, at others it has been carefully saved during times of conflict. Always, however, the women who created it seem to have been ignored. Indeed, its incorrect designation as as a tapestry rather than an embroidery can be seen as an attempt to separate it from women’s work. Its content focusses almost exclusively on men, with only six women appearing, and even today, visiting as a tourist, its exhibition leaves out any mention of its creators.

This is a sad occurrence which we see repeated time and again. Women were excluded from the London Guild of Broderers after the Black Death in an attempt to preserve the reduced number of commissions for men. This succeeded in de-professionalising the skilled women who worked in the field and relegated projects that came their way to much smaller, more menial work. When the sumptuary laws were revoked in 1630 embroidery was no longer considered a high art, losing its status as a symbol of wealth and power. This led men to draw away from it and to further divide men’s and women’s work, which became increasingly associated with family care and its virtues.

Embroidery enjoyed something of a revival in the eighteenth century with the popularity of thread painting. Despite some women succeeding in making a living out of it, very little of their work has survived. This is, unfortunately, a recurring pattern. The use of banners by suffragettes was an important part of their demonstrations yet when offered to Scotland’s museums they were rejected as having no historical value. Indeed, the National Museums of Scotland have only one stitched suffrage banner on display - for the Federation of Male Suffrage. Similarly, examples of embroidery by Mary, Queen of Scots, stitching at a time when embroidery was rich with hidden meaning and a symbol of status, are few and far between.

Embroidery has been used throughout history to create a sense of unity. Hunter’s work as a community textile artist has shown time and time again the value of creative expression and its power to bring fraught communities together. It helps to empower participants and gives them a sense of ownership over their story. This can also be seen in the moving examples detailed of its use in the most dire situations. Women in Changi Prison created quilts as an act of resistance and communication masked as a feminine act of care. During war it has often been used to record experiences and help to maintain a sense of self when attacked on all fronts.

This book is rich in historical detail and offers insight into beliefs around created pieces such as the spiritual power of joining fabric together, which was the traditional appeal of patchwork - resurrection, reconstitution, and re-connection. You learn not just about the role of sewing in social and political movements but of the events surrounding them. A trigger warning of torture and sexual violence for some sections. I wasn’t expecting a history of embroidery to be so emotional, but there are many moments throughout that will make your heart ache. An homage to an often-undervalued art, beautifully written and utterly compelling.